A nossa leitura corrente é A Good Man is Hard to Find (Oh, que grande verdade!!), uma colectânea de histórias de Flannery O'Connor. Cá estamos de volta aos clássicos.

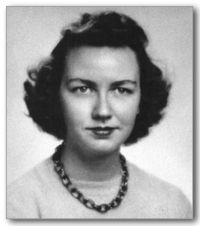

Aqui deixo um texto tirado da Wikipedia, a enciclopédia gratuita on-line, com uma informativa introdução à vida e obra da autora:

Biography

Mary Flannery O’Connor was born into an Irish Catholic family in Savannah, Georgia. She was the only child of Edward F. O'Connor and Regina Cline O’Connor. Her father was diagnosed with lupus in 1937; he died on February 1, 1941. The disease was hereditary in the O'Connor family. Flannery was devastated, and almost never spoke of him in later years.

Flannery described herself as a "pigeon-toed only child with a receding chin and a you-leave-me-alone-or-I'll-bite-you complex." As a child she was in the local newspapers when she taught a chicken that she owned to walk backwards. She said, "That was the most exciting thing that ever happened to me. It's all been downhill from there."

O'Connor attended the Peabody Laboratory School, from which she graduated in 1942. She entered Georgia State College for Women (now Georgia College & State University), where she majored in English and Sociology (the latter a perspective she satirized effectively in novels such as The Violent Bear It Away). In 1946 Flannery O'Connor was accepted into the prestigious Iowa Writers' Workshop.

In 1949 O'Connor met and eventually accepted an invitation to stay with Robert Fitzgerald (translator of Greek epic plays and poems, including Oedipus Rex and both the Odyssey and the Iliad) and his wife, Sally, in Redding, Connecticut. [1]

In 1951 she was diagnosed with disseminated lupus, and subsequently returned to her ancestral farm (see Andalusia) in Milledgeville. There she raised and nurtured some 100 peafowl. Fascinated by birds of all kinds, she raised ducks, hens, geese, and any sort of exotic bird she could obtain, as well as incorporated images of peacocks often in her books. She describes her peacocks in one essay.

Despite her sheltered life, her writing reveals an uncanny grasp of the nuances of human behavior. She was a deeply devoted Catholic living in the mostly Protestant American South. She collected books on Catholic theology and at times gave lectures on faith and literature, traveling quite far despite her frail health. She also had a wide correspondence, including such famous writers as Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop. She never married, relying for companionship on her correspondence and on her close relationship with her mother.

She died on August 3, 1964, aged 39, of complications from lupus at Baldwin County Hospital and was buried in Milledgeville, Georgia. Regina Cline O'Connor outlived her daughter by many years, finally dying in 1997 at the age of 99.

Career

An important voice in American literature, O'Connor wrote two novels and 31 short stories, as well as a number of reviews and commentaries. She was a Southern writer in the vein of William Faulkner, often writing in a Southern Gothic style and relying heavily on regional settings and grotesque characters. Her texts often take place in the South and revolve around morally flawed characters, while the issue of race looms in the background. A trademark of hers is subtle foreshadowing, forcing the reader to glaze over the red flags she places in her stories. Finally, she brands each work with a disturbing and ironic conclusion.

Her two novels were Wise Blood (1952) and The Violent Bear It Away (1960). She also published two books of short stories: A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories (1955) and Everything That Rises Must Converge, published posthumously in 1965.

A life-long Roman Catholic, her writing is deeply informed by the sacramental, and by the Thomist notion that the created world is charged with God. Yet she would not write apologetic fiction of the kind prevalent in the Catholic literature of the time, explaining that a writer's meaning must be evident in his or her fiction without didacticism. She wrote ironic, subtly allegorical fiction about deceptively backward Southern characters, usually fundamental Protestants, who undergo transformations of character that to O'Connor's mind brought them closer to the Catholic mind. The transformation is often accomplished through pain, violence, and ludicrous behavior in the pursuit of the holy. However grotesque the setting, she tried to portray her characters as they might be touched by divine grace. This ruled out a sentimental understanding of the stories' violence, as of her own illness. O'Connor wrote: "Grace changes us and change is painful." She also had a lively, sardonic sense of humor, often based in the disparity between her characters' limited perceptions and the awesome fate awaiting them. Another source of humor is frequently found in the attempt of well-meaning liberals to cope with the rural South on their own terms. O'Connor uses such characters' inability to come to terms with race, poverty, and fundamental religion, other than in sentimental illusions, as an example of the failure of the secular world in the twentieth century. However, she was not a reactionary: several stories reveal that O'Connor was familiar with some of the most sensitive contemporary issues that her liberal and fundamentalist characters might encounter. She was aware of the Holocaust, touching on it closely in one famous story, "The Displaced Person." Integration comes up in "Everything that Rises Must Converge," and O'Connor's fiction became more and more concerned with race as she neared the end of her life.

Her best friend, Betty Hester, received a weekly letter from O'Connor for over a decade. These letters provided the bulk of the correspondence collected in The Habit of Being, a selection of O'Connor's letters that was edited by Sally Fitzgerald. The reclusive Hester was given the pseudonym "A.," and her identity was not known until she died in 1998. Much of O'Connor's best-known writing on religion, writing, and the South is contained in these and other letters.

The Flannery O'Connor Award for Short Fiction, named in honor of O'Connor, is a prize given annually to an outstanding collection of short stories.

domingo, 1 de outubro de 2006

etiquetas:

Flannery O'Connor

Subscrever:

Enviar feedback (Atom)

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário